Michelle Chernick Hannah Alpert

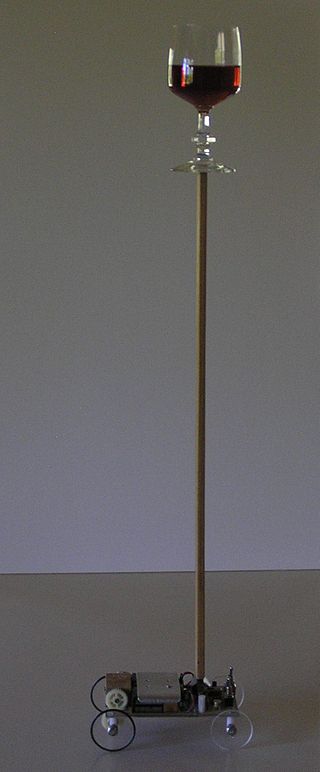

Can we get the wine to the teaching team without it spilling, as the cart traverses the hills of San Francisco?

Self-Stabilizing Platform

Project team members: Michelle Chernick and Hannah Alpert

Abstract

The purpose of this project is to model a self-stabilizing platform that would allow for efficient transport of food, fragile materials, and people. The platform adjusts its angle such that it remains flat relative to the surface on which it is traveling, according to the output of an accelerometer on the platform surface. This will keep food from spilling, fragile goods from breaking, and hospital patients from becoming more injured. The platform will change its angle via a linear actuator connected to an accelerometer. Our final controller design was a lead-lag compensator that aimed to keep the settling time below 5 seconds and the overshoot under 4.5 degrees in either direction. Our compensator successfully controlled the overshoot, settling time, and steady-state error. The final overshoot was less than 1 degree and the settling time was less than 10 seconds, and significantly shorter for angles close to 10 degrees.

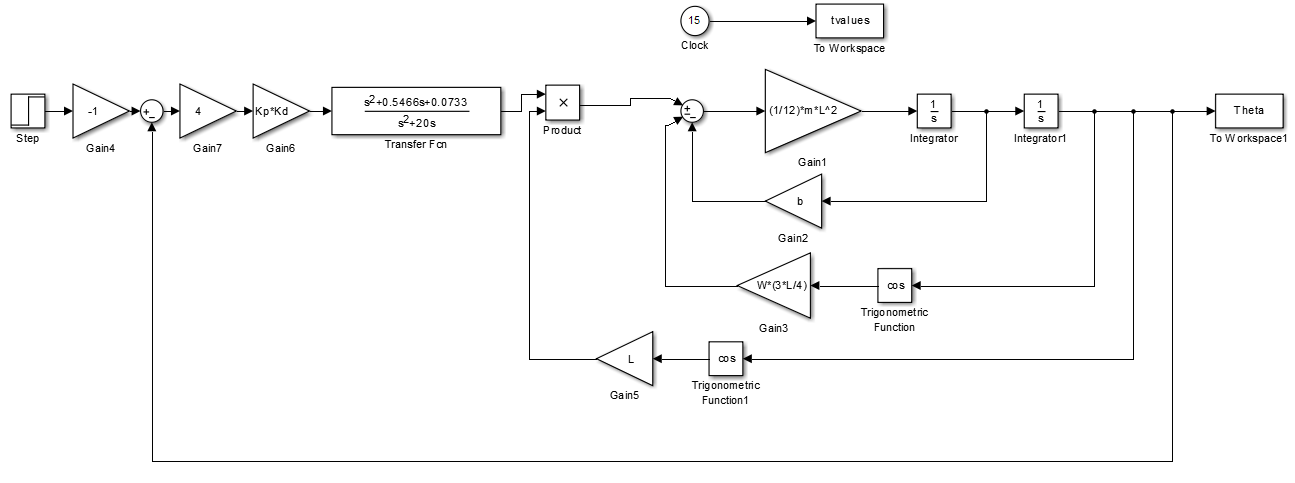

The advanced feature of our project is a Simulink model of our nonlinear system. There are multiple trigonometric terms in our equations of motion, which we did not linearize.

Introduction

Transporting food, fragile goods, and injured people often requires that the surface on which they sit remains level. Encountering bumps in the road and steep inclines could prove disastrous in certain situations. A self-stabilizing platform integrated onto rolling carts or vehicles would be an efficient solution to this problem, which would have many real-world applications. For example, catering companies could use the system when transporting food and beverages from their headquarters to a venue, and then wheeling the goods around the venue. Everyone has seen what happens when a pizza gets tilted on its way home from the pizzeria; putting the pizza on a platform that adjusts as the car goes up and down hills would avoid this problem. Also, UPS drivers often take inefficient routes to avoid big hills so that fragile packages remain upright. A self-stabilizing platform would be able to keep boxes in the preferred position regardless of the route. Finally, these platforms would be useful for transporting injured people on stretchers. Certain injuries, particularly of the back and neck, require that a person remain perfectly still and stable until they the hospital. Unfortunately, wheeling stretchers along the sidewalk may cause the person to jolt around, and riding in the ambulance poses similar threats. The system in our project would keep these people in a safe position during their transport to the hospital. Our self-stabilizing platform will adjust itself to stay flat so that food, goods, and people remain in the optimal position during travel.

Plant Model

1. Describe the model in words:

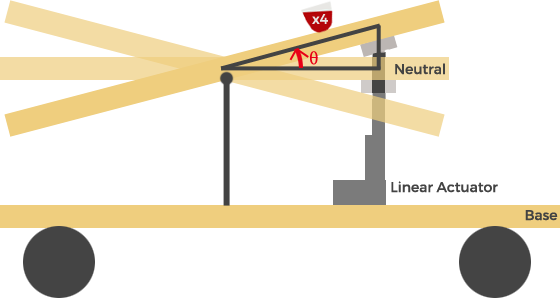

In our model, a platform is holding four glasses of wine to bring to the teaching team. In order to keep the wine from spilling as it traverses the hills of San Francisco, it is on a self-stabilizing platform. An actuator applies a force at the end of a platform to adjust the angle of the platform so that it stays flat. The desired angle is determined to be the opposite of the angle at which the platform is tilted, so that the platform returns to horizontal. The linear actuator is further modeled with a torsional damping constant.

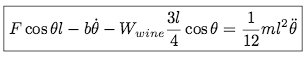

2. Time-domain equation of motion:

3. Block diagram of the open-loop system:

4. Derivation of your model:

LaTeX code describing the derivation of the nonlinear transfer function, in time domain:

Attach:AlpCher_derivation-equations-motion.pdf

5. Values of parameters of model:

- Length of platform (modeled as rod): L = 1 ft = 0.3048 m

- Mass of platform: m = 5 kg (approximate mass of wooden plank of given size)

- Torsional damping constant: b = 3 Nm/(rad/sec) (similar to values in other torsional systems)

- Mass of wine: m_wine = 1 kg (mass of bottle of wine, split into 4 glasses of course)

6. Results of simulation showing open-loop behavior of plant:

Simulink model, code, and output for open loop system

Attach:AlpCher_simulink-model-open.pdf

Control Design

1. Control approach in words:

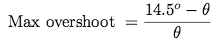

In our open-loop system, the platform settled to -pi/2 radians, essentially becoming a hanging mass or a regular pendulum. The maximum angle that the platform can tilt depends on the maximum height of the linear actuator. In our model, the linear actuator is able to extend 3" in either direction. The maximum tilt angle is thus 14.5 degrees. If the cart is going up a 10 degree slope, for example, the platform must tilt by 10 degrees in the opposite direction. Because the maximum amount of til is 14.5 degrees, in this case the maximum undershoot can be 4.5 degrees while the maximum overshoot can be 24.5 degrees. Since the maximum undershoot condition is significantly more strict, this is the value we must design for. In general form, the over/undershoot percentage is:

The maximum overshoot we would design for is 14.5 degrees, and at this angle, a wine glass that is 3/4 full will not spill, so this is a valid metric to use.

Another metric we need to take into account is the settling time. In the open-loop system the settling time is over a minute; this is much too long to say that it has successfully returned the platform to horizontal. We would like the system to stabilize within 5 seconds.

2. Mathematical description of controller:

We initially tried using a PID controller of the form:

After iterating, we found that a lead-lag compensator had significantly improved performance, and thus our final controller was of the form:

The final controller, which will be discussed in detail later, was:

3. Block diagram of closed-loop system:

4. Derivation of controller parameters and design process:

Attach:AlpCher_control-design-process.pdf

Results

The input signal to our system is the angle of the hill that the cart and self-stabilizing platform are driving over. The output of the controller is F, the force that the linear actuator should exert to cause the platform to adjust by the same angle as the hill. The output signal of the block diagram is the angle by which the platform adjusts, and this should match up with the angle of the hill.

The block diagram of our system is shown below.

The response to a step input of 10 degrees is as follows:

The overshoot is 0.88 degrees and the settling time is 1.7 seconds, well within the bounds we set.

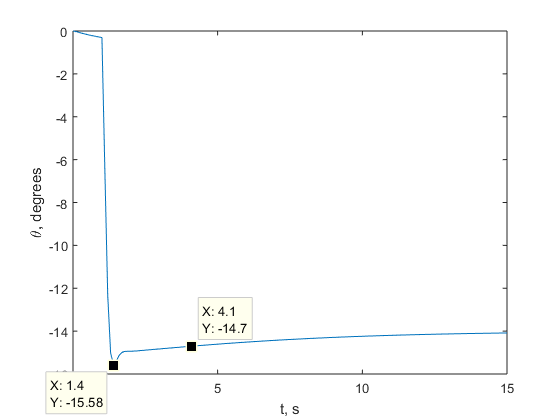

The response to a step input of 14 degrees is below:

The overshoot is 0.58 degrees and the settling time is 4.1 seconds, still within our bounds.

The response to a step input of 8 degrees is slightly worse:

The overshoot is 0.988 degrees, but the settling time is 7.4 seconds, which is above what we were aiming for. However, if our settling time error band was changed to be within 10% of the final value (which equates to just 0.8 degrees) then the response time is 1.6 seconds. We think that being within 10% of the desired angle is reasonable because it is less than 1 degree.

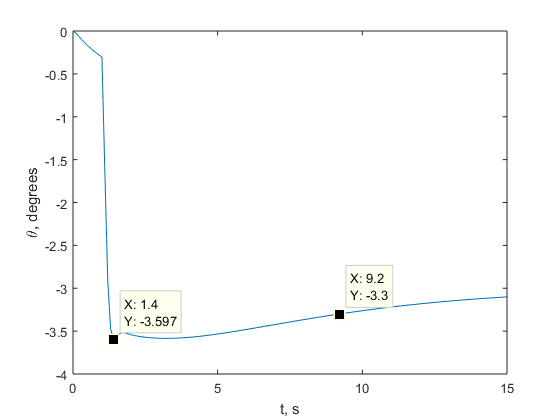

The response to an input of 3 degrees is:

The overshoot is 0.597 degrees and the setting time for a 10% error band (0.3 degrees) is 9.2 seconds; although this is not quite as good as the larger angles, it is still acceptable because the angle is so small so the wine will still not spill.

Conclusions

Overall, we were satisfied with the final controller we designed. For the most part, the settling time was less than 5 seconds and the overshoot was significantly less that 4.5 degrees. The settling time of the system got worse as the angle of the hill decreased; however, at such small angles, it would not cause the wine to spill if the platform took slightly longer to achieve the correct angle, so we are satisfied with this behavior. One limitation of our system is that because the actuator is only 3", the maximum angle the platform can tilt is 14.5 degrees. There are higher-quality linear actuators that have a larger range of motion, but a 3" actuator is sufficient for most hills in San Francisco. If we had more time to work on this, we would continue to iterate on our lead-lag controller. Also, we would try to design for inputs that are more realistic than step inputs. For example, a ramp input would model a hill with a changing inclination.

Acknowledgments

Huge thank you to Allison and the whole teaching team for helping us out on this project. We're sorry the glasses of wine aren't real.