James Lauren

BurnAlert: A ThermoHaptic Device

Project team members: James Ortiz and Lauren Killingsworth

BurnAlert is a wearable haptic device that vibrates when the user touches a hot object. Worn on the hand, this device consists of four temperature-sensing thermistors that are strapped onto users' fingers and a wristband containing a vibration motor. The idea for this device arose from the need for a reliable alert system for patients with medical conditions that impair their ability to sense temperature and pain. We undertook this project hoping to create a portable device that would vibrate upon immediate contact with a hot object at an intensity that varied with the temperature and proximity of the object. In relation to these initial goals, we achieved moderate success. Our BurnAlert prototype is portable; however, it vibrates only after prolonged contact with a hot object at a constant intensity. Despite these limitations, we believe that if several hardware and software improvements are made, this device will have the potential to be implemented on a larger scale.

On this page... (hide)

Introduction

BurnAlert designers Lauren and James.

We were inspired to design BurnAlert to address the medical condition of congenital insensitivity to pain (CIP). We remembered reading a New York Times article back in 2012 about the hazards of this condition. Titled "Ashlyn Blocker, The Girl Who Feels No Pain", this article brought national attention to the issue of congenital insensitivity to pain (CIP), which weakens the strength of pain signals due to a mutation in gene SCN98 (Heckert 2012). The article opened with a short narrative, recounting the time thirteen-year-old Ashlyn dropped a spoon in a boiling pot and reached in to grab it without thinking. She felt no pain, and it wasn't until she noticed the red inflammation of her hand that she realized she had burned herself. As evidenced by this article, there is a need for a temperature sensitive alert system, and we felt that haptic vibration feedback would fit this role perfectly. We envisioned a wearable haptic device that would alert users of dangerously hot temperatures through vibrations applied to the wrist. Unlike audio or visual alerts, vibration alerts provide haptic sensations in the same way that a healthy human nervous system provides haptic sensations upon contact with hot objects. Furthermore, if users are distracted, vibrations will warn them of contact with a hot object more effectively than audio or visual cues. While this device is meant to address CIP, we also see it being implemented on a broader scale to address the symptoms of peripheral neuropathy, a condition that affects over 20 million Americans (Neuropathy Association 2014). This disease results in a loss of sensation in the hands and feet, increasing the risk of trauma and burns (Mayo Clinic Staff 2014). Ultimately, BurnAlert is a prototype for a wearable device that may one day improve the safety of those suffering from a loss of pain and temperature sensations.

Background

To the best of our knowledge, there are no previous studies on haptic thermo-sensitive warning systems for peripheral neuropathy or CIP patients. However, there are a few studies that suggest methods of incorporating temperature sensing into haptic devices. Most relative to our project is a study on the design process of thermo-sensitive fire fighter gloves, "A Cognitive Glove Sensor Network for Fire Fighters" (Breckenfelder and Mrugala et. al 2010). This paper proposes a device that uses wireless sensor nodes (integrated in firefighter gloves) to take temperature readings. The glove transmits haptic feedback in response to unsafe environmental conditions, issuing temperature warnings and messages to retreat from the fire. Haptic feedback is transmitted through two vibration motors. This paper focuses on analyzing the psychological aspects of using a haptics temperature warning system, to determine if the firefighters would trust the device, and how well they would adapt to this additional "sense" (Breckenfelder and Mrugala et. al 2010). As of 2010, the product was in the very beginning design stages, and plans were being made to build a first prototype. Breckenfelder and Mrugala et. al have not published an update since. Other researchers and companies have suggested applications of haptics in temperature sensing. Precision Microdrives, an electric motor supplier, suggests that students experiment with how to wirelessly warn of unsafe temperatures (Precision Microdrives 2014). This concept is very similar to our device, though, like the previously discussed paper, its motivation is to help those facing extreme heat in the workplace. Another study that integrates temperature sensing with haptics is Touch: Sensitive Apparel (Abbas and Vaucelle 2007). This prototype involves attire that compresses and expands depending on temperature. Though it could potentially be used to alert users of dangerous temperatures, the main focus is on massage and comfort capabilities. We also identified a few haptic alert systems that respond to unsafe body conditions. For example, a patent application for a "Haptic health feedback monitoring system" proposes a device that alerts users with haptic feedback if their heart rate is dangerously high (Ramsay, Heubl and Olien 2010). BurnAlert is similar in that it provides haptic feedback to alert users of unsafe body conditions—in our case, temperature.

Software Background: We found the code to convert the raw data from the thermistors into temperature readings (in oF) on the Arduino website (Arduino 2014). We used the code from the Hapkit labs to set the PWM frequency (Okamura 2014).

Design

Hardware design

Overview

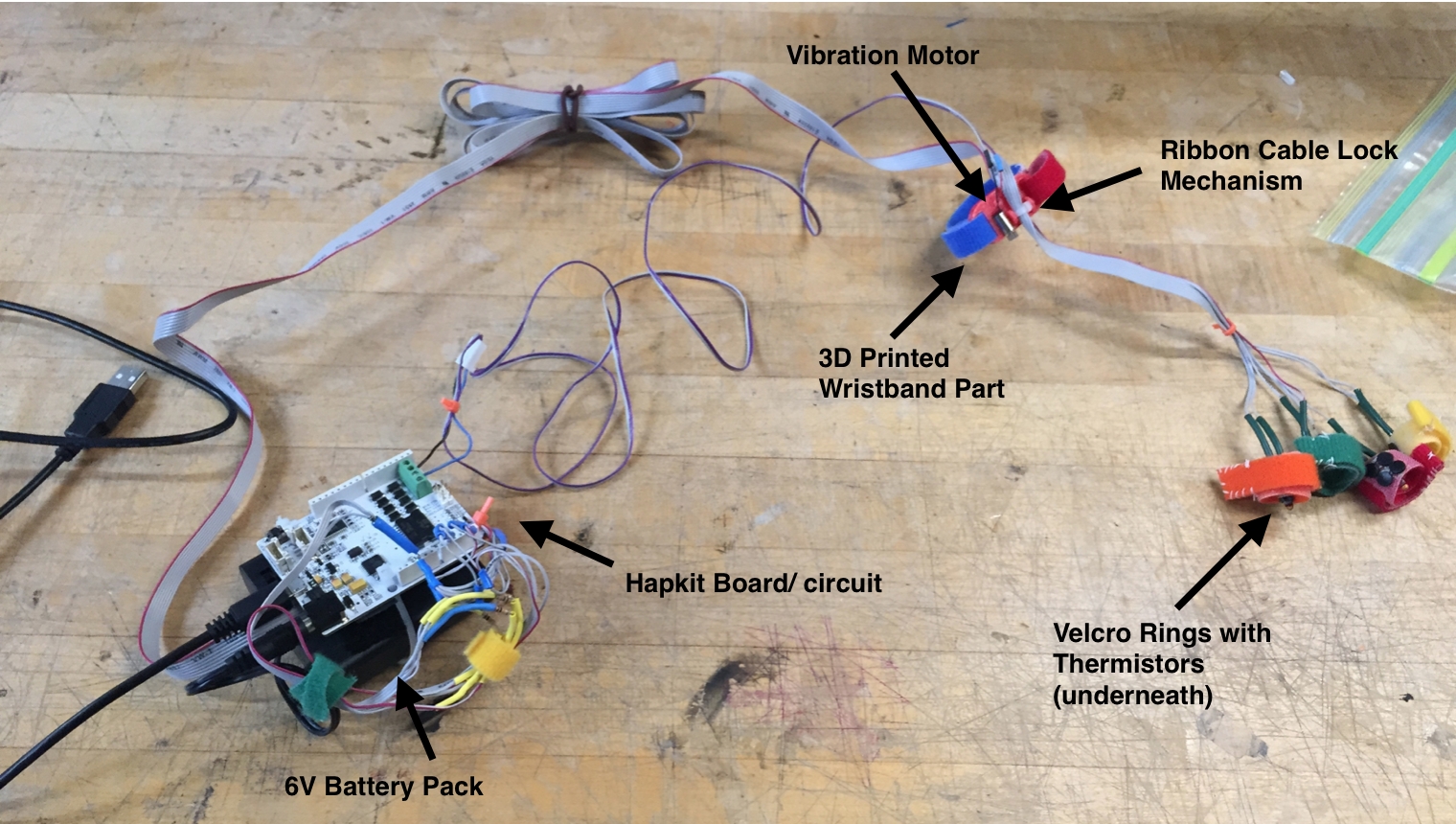

Wearable thermistors are attached to the user's fingers. The ribbon cable from the thermistors is threaded through the 3D printed wristband device, which contains the vibration motor (see Fig. 1). The vibration motor wires and ribbon cable are attached to the parallel circuit of the Hapkit board. A 6V battery pack is connected to the Hapkit board.

Fig.1: BurnAlert hardware components.

Wearable Thermistors

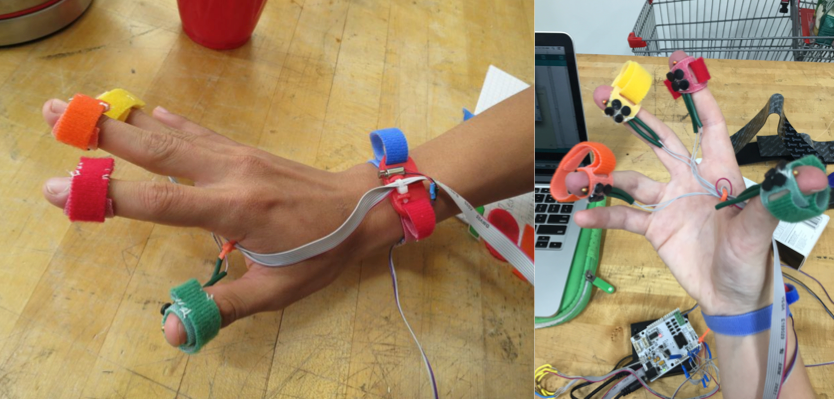

Thermistors are temperature dependent resistors. We use 4 10K thermistors to sense temperature, which are connected to the Hapkit board (as described in "Circuitry"). The thermistors are soldered to the wire cable and extra long shrink tube is used to protect the wires from damage. The wire cable extends from the fingers, through the lock mechanism on the 3-D printed device (see "3D Printed Wristband Part"), then to the Hapkit board. Our initial design included a glove with attached thermistors. However, we realized that a glove may be inconvenient or uncomfortable to wear on a daily basis. We thought that finger rings containing thermistors would be more practical for everyday use. The thermistor ring design also evolved throughout the project. We decided on putting temperature sensors on the thumb, index finger, middle finger, and ring finger because the pinky finger is rarely the first finger to contact objects. 5 thermistors would have required another hapkit board, which would increase the size of the portable device. We initially bent the thermistor wires around the shape of the finger. This posed the issue of wire fatigue and breakage, so we looked for other options. We decided on a Velcro, slip-in ring device. 1.3 cm width Velcro bands with small slits were obtained. We looped the Velcro through the slits then cut it to the appropriate length. We used 7cm as the maximum finger circumference (this number was obtained by measuring classmates' fingers as well as researching finger circumference ranges online). The Velcro can be tightened to fit any finger. The soft side of the Velcro is on the inside of the ring, against the finger. In order to attach extra Velcro material to the ring, the end of the Velcro is folded back into a tab with the rough edge facing the soft edge. High strength, plastic coated thread was used to sew these tabs in place. The thermistors (within the shrink tube) are secured directly under the finger, approximately 5mm away from the slit (Fig. 2). The thermistors are attached with high strength thread, which was looped around the individual thermistor wires as well as both of the wires. The tip of the thermistor, the temperature sensitive region, is just outside of the Velcro ring. The ring rests on the upper part of the finger, above the interphalangeal joint (the second joint on the finger). Small rubber circles were added to allow the wearer to grip objects, as the Velcro provided little traction. Small circles were used instead of larger pieces, in order to improve flexibility and efficacy of the gripping capabilities (Fig. 2).

Fig.2: BurnAlert wearable thermistor velcro rings (left) and rubber grips for traction (right).

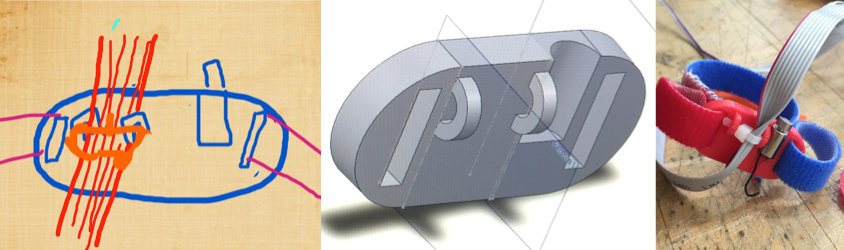

3D Printed Wristband Part

We designed a wearable part in SolidWorks to hold the vibration motor and secure the ribbon cable wire that stretches from the tip of the fingers to the Hapkit board (Fig. 3). We designed a rounded rectangle shaped part with two 1.4 cm slits on the sides. The part is 4 cm at its greatest length and 2 cm at its greatest width. Velcro was threaded through these slits then attached to the Velcro on the outside of the wrist. The wrist part was therefore made adjustable. The part also includes an indentation that is one half of a cylinder. This provides a small divot for the vibration motor to securely sit in. It is designed to fit the 1.2 cm length of the vibration motor and the 3mm radius. The vibration motor was secured in the part using super glue. Two arches were designed as a way to secure the ribbon cable. The ribbon cable was tightened with a zip tie, and the long end of the zip tie was then looped under the arch. If the ribbon cable is tugged, it will not break this attachment. This adds an extra security measure to ensure that the circuitry is not broken. The wires that thread through this arch system are then attached to the Hapkit board.

Fig.3: Initial sketch of design (left), Solidworks design (middle), and 3D printed part with motor and ribbon cable (right).

Circuitry

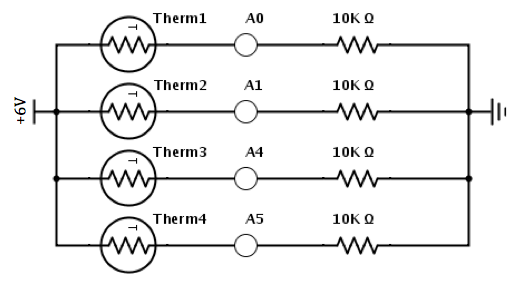

We designed a parallel circuit (Fig. 4) to connect the four thermistors and the four 10K Ω resistors to the voltage source, ground, and analog input pins. In order to build this circuit, we soldered the ends of ribbon cable to the different electronic components. Since the ribbon cable wire was too thin to insert into the pins directly, we soldered this wire onto thicker, stronger wire that would then be inserted into the pins. The path of this circuit was designed so that the current would travel from the voltage source to the thermistors then to the analog input pins then to the resistors and finally to ground. The thermistor on the thumb was connected to pin A0, the one on the index finger to pin A1; the one on the middle finger to pin A4; and the one on the ring finger to pin A5. Additionally, the vibration motor was connected to the motor 1 terminals on the Hapkit board.

Portable Battery Pack

The Hapkit Board is secured to a 6V battery using zip ties and Velcro. The ribbon cable is fastened to the Hapkit board with a zip tie to ensure that, if stress is applied, the circuitry will not be broken. The ribbon cable is looped under the Hapkit board and is attached with industrial strength Velcro to the board. The board is attached with industrial strength Velcro to the battery pack and zip-tied around the pack. Wires are grouped together and attached with Velcro to make device as compact as possible and to avoid entanglement. The battery pack and haptic board device can fit in most pockets.

Software design

The code achieves two basic functions: 1) it converts the raw data from the thermistors into temperature readings (in oF) and then prints them to the Serial Monitor and 2) it causes the vibration motor to vibrate when the temperature reading of at least one of the thermistors is above 85oF. Since we used a 6V battery pack and a vibration motor that operates at 1.3 V, the code implements a duty cycle of 10% to output 0.6V to PWM pin D5—the pin corresponding to the vibration motor—whenever one of the thermistors goes above 85oF. This voltage output yields a noticeable and comfortable vibration for the user.

Functionality

At the Haptics Open House demo, we had users attach the finger straps to their thumb, index, middle, and ring fingers (Fig. 2). We then asked them to wait for a couple of seconds to allow the thermistors to register their body temperatures (on average, the thermistor readings for the users' body temperatures were around 80oF). Then, users were instructed to hold a plastic cup containing hot water until at least one of the thermistors heated up past 85oF (~1 min), after which the motor on the wrist piece would begin to vibrate. Once the motor began to vibrate, we instructed users to put down the hot cup and hold a cup of ice water until all of the thermistors cooled down below 85oF and the motor ceased to vibrate. Throughout the demo, users were able to observe the temperature readings of the four thermistors via the Serial Monitor.

There are several major hardware and software improvements that could be made to this device. In terms of hardware improvements, the most important one is to obtain thermistors that heat up and cool down fast enough for immediate and responsive vibration feedback. Currently, our thermistors are a major limitation in our device because users must grasp a hot object for about a minute before receiving vibration feedback and must let the thermistors cool down for about a minute before the vibration stops. This means that the alerts are too prolonged and not immediate enough to serve as a preventive measure. Another important improvement is to use more durable vibration motors, as the one that we are currently using is liable to burn out. Moreover, we suggest that an additional wearable thermistor for the pinky finger be added to the device. In terms of software improvements, we suggest increasing the vibration intensity as the temperature of the hot object increases in order to give users a sense of urgency to withdraw their hand when they touch a hot object.

BurnAlert in Action:

Explanation: The user starts off by holding the cup of ice water to cool the thermistors below 85oF so that the motor stops vibrating. Then, he proceeds to hold the red cup of hot water to heat up the thermistors above 85oF. Although it is not too clear in the video, by 0:11, the motor is vibrating.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Jeanny Wang for teaching us about Solidworks design and for answering all of our questions about 3-D printing. We would also like to thank Akzl Pultorak for his support with Solidworks. We are especially grateful for Professor Allison Okamura's assistance and guidance throughout the design and engineering process.

Files

- 3D Printed Wristband Part Solidworks File: Attach:finalhaptics.SLDPRT.zip

- 3D Printed Wristband Part STL File: Attach:finalhaptics2.STL.zip

- Arduino Code: Attach:FinalHapticCode12_11.ino.zip

- Materials List: Attach:HapticsMaterials.xlsx.zip

References

- Abbas, Yasmine and Cati Vaucelle. "Touch - Sensitive Apparel." MIT Media Laboratory. 2007.

- "Ashlyn Blocker, The Girl Who Couldn't Feel Pain." The New York Times. 15 Nov. 2012. Web. 11 Dec. 2014.

- Breckenfelder, Christoff, Damian Mrugala, Chunlei An, Andreas Timm-Giel, Carmelita Görg, Otthein Herzog, and Walter Lang. "A Cognitive Glove Sensor Network for Fire Fighters." Workshop Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Intelligent Environments: 158-169. 2010.

- Okamura, Allison. "Lab Assignment 7: Something New." Haptics: Engineering Touch. Stanford University, Stanford CA: 2014.

- "Peripheral Neuropathy." Mayo Clinic. 02 Dec. 2014. Web. 11 Dec. 2014.

- Ramsay, Erin, Robert Heubel, and Neil Olien. "Haptic Health Feedback Monitoring." Immersion Corporation, assignee. Patent EP 2155050 A1. 24 Feb. 2010. Print.

- Malesevic, Milan and Stupic, Zoran. "Reading a Thermistor." Arduino. 2011. Web. 11 Dec. 2014.

- "The Girl Who Can't Feel Pain." YouTube. ABC News, 3 Sept. 2012. Web. 11 Dec. 2014.

- "Wireless Feedback Example Applications: Wireless Temperature Warning." Precision Microdrives. 2014. Web. 11 Dec. 2014.