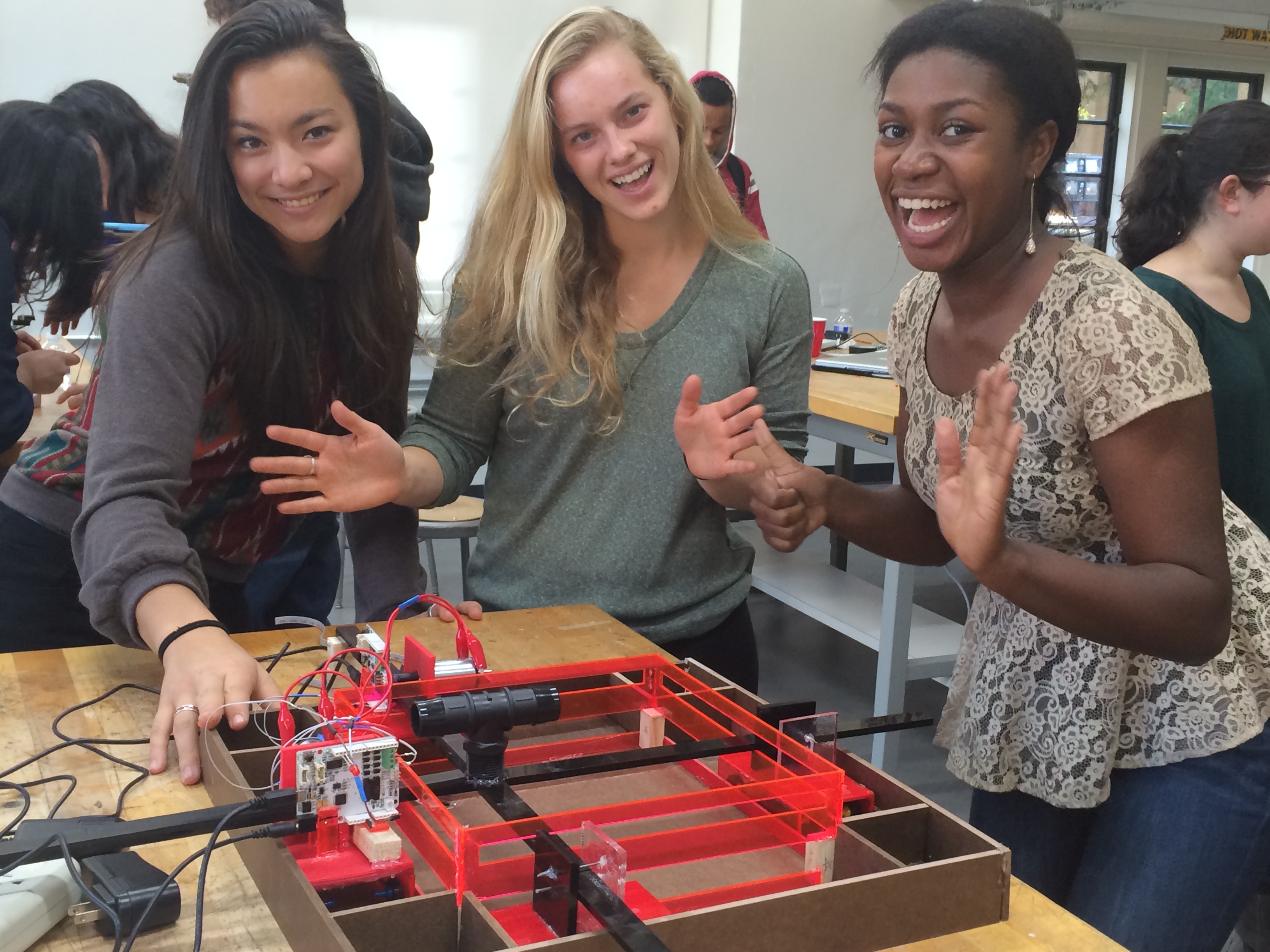

Jite Madelyn Maika

The finished Haptamaze.

Haptamaze

Project team members: Maika Isogawa, Madelyn Boslough, and Jite Ovienmhada

Introduction

The Haptamaze: an adaptable haptic device with two degrees of freedom which uses force feedback and computer graphics to create a tangible virtual maze. Although the Haptamaze currently only functions for entertainment, our goal in building it was to learn enough about creating compelling haptic virtual environments that we could eventually expand the underlying concepts to more functional applications (see Functionality, paragraph 1).

Background

When we were turned loose to design our own unique haptic device, we knew only two things for sure: first, that we wanted to work in the Product Realization Lab a lot; and second, that we wanted to provide a variety feedback types for the user. These very basic guidelines came together in the form of the Haptamaze, a virtual maze that the user navigates using force feedback and visual feedback from a computer screen. The device operates in two degrees of freedom, so the mechanical component was large and complicated enough to keep us in the PRL for plenty of long hours. We accomplished our second goal by combining force feedback with a synced computer-programmed visual of the maze, an LED that lit when a wall was contacted, and a sound that accompanied the first tap of the walls.

Design

Hardware design

The mechanical design consists of four wheeled carts rolling on the outside of a square frame. Two of the carts are active—they hold the two motors and Hapkit boards, while the other two carts are passive—they simply roll in tandem with the motor-carrying carts. The frame consisted of four acrylic walls with thin rectangular slits cut in them. The user interacts with this device by way of a handle attached to the center of a long acrylic cross. The arms of the cross extend through the slits of the frame to connect to the carts. The arms connecting to the active carts are tipped with neoprene and roll over the axons of the motors, also tipped with neoprene. Each motor is mounted opposite a Hapkit board, and has a magnet attached to the tip of its axon which faces the magnetoresistive sensor (MRS) mounted on the back of each board. As the user moves the handle within the frame, the cross arms roll over the motor drive wheel, rotating the magnet. The MSR uses the change in magnetic field to relay position data. One active cart is responsible for the horizontal position tracking, and the other for the vertical position tracking. The passive carts, which move parallel to the active carts, have wheels that mimic the motor axons to stabilize the system. To reduce friction and prevent the carts from sliding sideways, all of the moving parts and the inner frame are mounted on a large, walled Duron board.

Electronics Design:

The Hapkit board on the y-axis was used as the master, the x-axis Hapkit board was used as the slave. To send the x-position from the slave board to the computer, the slave board was connected to the master board using the A2 and A4 pins. To run the slave motor based on output information from the master board, the slave motor was connected directly to the D6 and D7 pins on the master board. The code organized the input and output of the information from the pins. The wires were soldered to assure a secure electrical connection. One difficulty was keeping the wires from tangling in the mechanical design, or getting unplugged by the moving carts. To solve this, the wires were taped together, and run over the top of the Haptamaze.

Software Design

The software component of the Haptamaze was developed in two different applications : Arduino and Processing.

Arduino

The programming done in Arduino does 2 main jobs. It is responsible for position tracking of the user and outputting a force to the motors. As explained in the hardware, the physical design of the position tracking feature consists of a MSR that reads the number of times the magnet flips as the user rolls their arm over the drive wheel. In Arduino, the number of flips translates to a number of counts. We wanted the origin (which in our case is the top left corner of the frame) to be our zero and for the Arduino world to have a sort of virtual 500 by 500 grid. This wasn't absolutely necessary but would make it easier to manipulate numbers later. To do this, we calibrated the position using linear regression on a graphing calculator to find a line of best fit. The location of the virtual walls were set to be the exact coordinates of the graphical walls in Processing. However, these coordinates can be changed with some tedious tweaking. (In hindsight, a better way to make the virtual walls readily changeable would have been to define them as constants.) The force calculation is a variation of Hooke's law that defines a stiffness to output to the motors in Newtons per meter.

Processing

The programming done in Processing was solely created for aesthetic purposes. It serves only to create a more compelling virtual world. Processing reads the x and y coordinates of the user from Arduino over the serial monitor and a red rectangle (that represents the user) moves in conjunction with the user's movement of the handle as the user navigates the maze. When the user hits a wall, a thumping sound plays. The virtual walls were set to be the coordinates of the borders of the rectangles. These are the numbers that were used in Arduino to identify if the user had hit a wall (which is why creating a grid of sorts in Arduino to match the Processing grid was useful).

Functionality

The Haptamaze is in its current stage a very simple device to interact with. The user takes the handle and guides it through a maze, testing walls gently and using the force feedback to navigate. They can also make use of the maze computer graphics and LED visual feedback if desired.

However, the mechanical components and the two-degrees-of-freedom position sensing code already in place make the Haptamaze a highly adaptable device. We could naturally expand to more complex mazes, or use it for other games. Different damping and textures could be programmed in to create a complex, compelling haptic environment for a user to explore. For example, using damping, textures, and walls, the device could be programmed to represent a topographic map as we initially envisioned.

Improvements

At the open house, people seemed enthusiastic about the Haptamaze although its actual functionality was simplistic. The feedback we received from users was encouraging, mostly just suggestions of how to debug and modify the original code to improve the motor feedback. Although the mechanics worked better than we expected, there are numerous small ways in which they could be improved. These minor issues occurred because the mechanics also proved to be more complicated than we had expected, so we had to improvise solutions to several issues that cropped up along the way. One of the biggest was the cart size, which prevented us from utilizing the frame space as we had intended because the carts ran collided at the very end of their paths. Smaller carts would have minimized this problem and maximized use of the space. We also had to improvise a last-minute support on the end of one arm to stabilize the handle. If we had been able to build a wheeled support in time, it would have reduce friction of the system greatly. The electronic wiring could also have been improved by increasing the length of the wires so that they could be more easily kept out of the way of the cart and handle motion.

The biggest issue that came up was the fact that the motors were tripped easily if a user pushed too hard against a virtual wall. We fixed this on the spot by resetting the Hapkit boards and Processing program, but eventually the code will need to be adapted to prevent this from occurring. At this point we are not entirely sure which portion of the code needs to be adapted, but we will update this page when we have pinpointed the issue.

How it's used:

Acknowledgments

Thanks so much to Allison for giving us the opportunity to do this project, and also for her help as we designed, built, and coded. A big thank you to her student assistants as well, particularly Jeanny for all the time she spent on this class and especially for helping us learn to use SolidWorks. Big thanks to Akzl Pultorak and Rishi Bedi as well. Akzl helped us with SolidWorks and Rishi responded to a late night email to come help us work through some major programming issues in the classroom at 11 pm! Thanks to the awesome Product Realization Lab TAs for their patience with teaching us to use all the equipment in Room 36 and the wood shop. Finally thanks to everyone in the class for being super supportive and inspiring us with their amazing projects! Our project would not have been possible without all of the help we received from so many different sources!

Files

- Attach:solidworks.zip The SolidWorks and STL files used for the carts

- Attach:HaptamazeGraphics.zip The Processing file used for graphics

- Attach:HaptamazeArduino.zip The Arduino file used for programming the Arduino Uno board

References

http://helpx.adobe.com/pdf/illustrator_reference.pdf http://arduino.cc/en/Reference/HomePage