2024-Group 10

Haptic Ghost Maze device and visualization

Handheld Ghost Marble Maze with Haptic Feedback

Project team members: Megan Coram, Melissa Klein, Sehui Jeong, Katie Marusich

Our team built an interactive game in which the player must learn to rely on haptic feedback to navigate a marble through a maze. In the first few levels of the game, the marble is visible, and the user can learn to associate the marble’s motion with the corresponding haptic cues. In the later levels of the game, the marble disappears from the virtual rendering and the user must rely only on haptic feedback to determine the behavior of the marble. In this project, our team intended to create a haptic system that was fun and engaging to interact with. We wanted to illustrate to users how haptic feedback can be used to assist navigation when sight is unavailable. At the Haptics Open House, users found the game to be challenging yet enjoyable.

On this page... (hide)

Introduction

On the surface, the purpose of this device is to demonstrate how haptics can be used in games and entertainment to complete a fun task. However, it can also serve to illustrate how haptics can be used to convey control feedback when visual feedback is unavailable. This sort of training could be useful for the operation of robots which work in low-light environments or in situations where vision is occluded. For example, grasping robots often encounter this difficulty when the grasper itself blocks the controller’s view of the target object to be grasped. In systems like these, haptic feedback could provide the operators with a tactile sense of where the robot is located and how it is moving in its environment, just as our users will get the impression of the invisible marble.

This device fulfills these purposes by being ergonomic and lightweight, by providing salient haptic cues, and by being engagingly interactive. Our team worked carefully to tune all of the haptic elements to provide the best response and to tailor the difficulty of the game to provide a fun but challenging experience to the players. Our device provides a fast-paced routine which both trains and tests players’ ability to learn, understand, and act based on haptic cues.

Background

Haptics has been widely explored for its utility in increasing engagement in and enjoyment of virtual games. Hamam et al. (2012) found that haptic feedback improved the Quality of Experience in multimedia applications. Seo et al. (2010) created a virtual billiards game with haptic feedback, and Park et al. (2009) added haptic interaction to a brickout game. According to the researchers, haptic feedback made these games “more realistic and pleasurable,” “more fun,” and more “intuitive” to the players.

Our project aimed to build a marble maze game with realistic haptic feedback to enhance the user experience. One of the key aspects of haptic feedback is perceiving the location of the ball. Kim et al. (2009) introduced a vibrotactile rendering method using two vibrational motors at the ends of a mobile device. By attenuating the amplitude of each motor, they could control the vibrational signal to create the illusion of a ball's movement on the device's surface. Our group drew inspiration from this work in creating the vibrotactile feedback in our device.

Visualization is also crucial for gameplay. Rose et al. (2017) developed a dynamic model for a ball and beam system designed for educational platforms. This model, which includes parameters for the ball's velocity and acceleration based on the beam's angular position, helped to inform the physics engine of our game. Huang et al. (2002) demonstrated the importance of haptic feedback in improving user performance in dynamic tasks, such as rolling a ball to a specific location by tilting the beam. They provided a dynamic model with a configuration similar to our device.

Finally, Swindells et al. (2003) presented the TorqueBAR, an ungrounded haptic feedback device that simulates dynamic inertia. They used a moving component to change the center of mass for realistic haptic feedback. Although our design will not include moving components, we were inspired by this work to include a solenoid that can physically tap the board to generate the illusion of contact between the ball and the walls and floors.

Methods

Hardware Design and Implementation

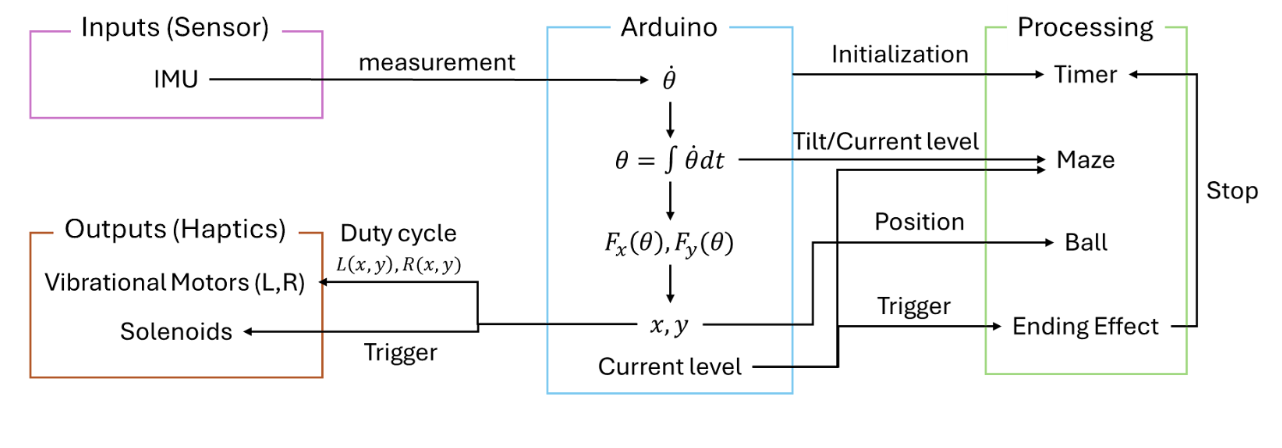

The physical system is housed on a laser cut board with 3D-printed handles for an ergonomic grasp. Holes were cut in the board to allow for convenient mounting of the electronic components. Two vibrational motors embedded in the handles are driven by the motor channels of the Hapkit Arduino board. This positioning was chosen to maximize the user’s ability to feel the haptic feedback. The MPU 6050 chip, which measures the tilt angle of the device, is placed in the center of the board so that the measured angles are as accurate as possible. The tilt angle code draws from the “basic_readings” example in the Adafruit MP6050 Library. A 5V solenoid was selected to generate the tapping effect when the ball hits the walls of the maze because that is the maximum voltage available on the Arduino board. The solenoid is placed in a custom mount with a plate for it to strike against in order to generate a tangible shock. Initially, the solenoid would also generate a small tap due to an internal collision when it moved in the other direction, so a small rubber o-ring was added next to its spring to dampen that effect. The solenoid is controlled using a transistor, and the circuit includes a dimly lit LED to indicate when the solenoid is engaged.

System Analysis and Control

Marble Virtual Environment Dynamics

In our virtual environment, a marble rolls on a tilted floor. In this system, forces from gravity, friction, and contact forces from maze walls were modeled.

The following diagram shows the system and free body diagrams of the virtual marble in three conditions: 1) when the marble is in contact with the left wall, 2) when the marble is not in contact with any wall, and 3) when the marble is in contact with the right wall. A Newtonian reference frame (x is horizontal and y is vertical) and a secondary reference frame (defined by x’ and y’) which is offset by a right hand rotation of theta from the global reference frame.

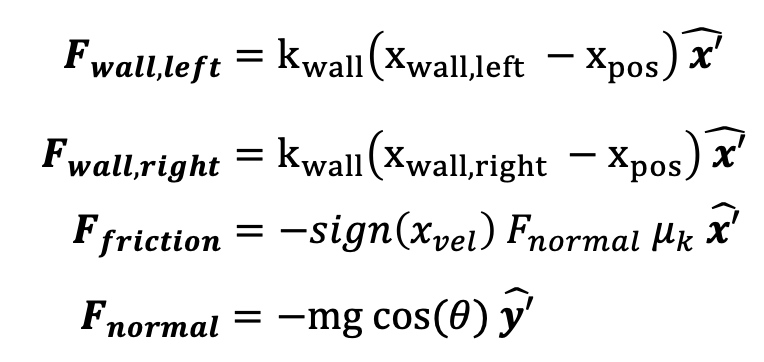

The walls were modeled as a spring-damper system which the marble interacted with when it’s position was “inside” the wall. The following equations describe the magnitude and direction in which each force acts:

The following values were chosen for the mass, coefficient of friction, wall spring, and wall damper after tuning to create a realistic simulation:

- Marble mass, m = 1 kg

- Coefficient of Friction, mu_k = 0.002

- Wall spring constant, k_wall = 100,000 N/m

- Wall damper constant, b_wall = 500 N s/m

- Gravitational Acceleration, g, = 9.8*5000 m/s (modified for graphics)

To prescribe motion such that the marble was always in contact with the ground, the y’ acceleration is set to zero, giving the following equations of motion:

Converting acceleration to the global reference frame:

The accelerations in the x and y directions were integrated with each update of the angle theta to get the current x and y position.

These x and y values were mapped to the virtual environment to display the marble during the game using the following equation for the marble position vector, which are functions of the current game level and the total number of levels:

The game levels are stacked vertically, with higher levels lower on the screen. While this was a modular variable, our game had 7 levels. When the level transition criteria are met, the ball falls through the floor to the next level.

To make this game challenging and fun, we set position and velocity criteria for moving on to the next level.

- The marble must be positioned over the hole

- The marble velocity must be under a specified threshold.

If the criteria were not met, the ball would continue to roll over the hole and not fall through.

We tuned the velocity threshold (2000) based on the difficulty of gameplay. This ensured that passing a level was reasonably possible while making it more difficult than merely tipping the device as quickly as possible in the direction of the hole.

Once the user reaches the level known as “ghost mode”, the marble is no longer visualized on the screen, although all of the marble dynamics are still computed by the Arduino.

Software Design

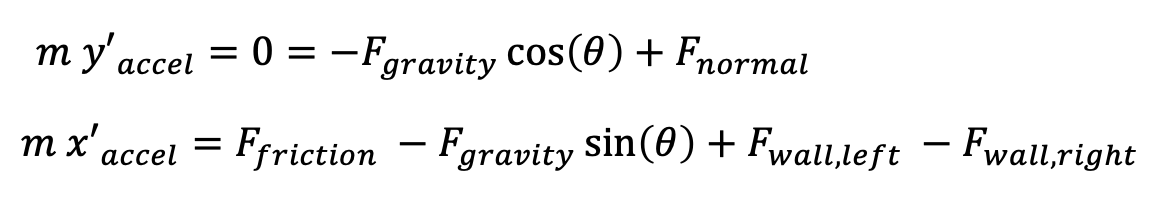

The dynamics are fully calculated in Arduino, and the necessary values for visualization are sent to Processing through serial communication. Processing then visualizes the maze, ball, and the timer.

From the IMU module, the Arduino receives the angular speed of the board, which can be integrated to calculate the tilt of the board. For the calibration, Arduino averages the first 1000 measurements to zero out the y-acceleration when it is sitting on a flat surface. Arduino then calculates the force in the x- and y- directions depending on the tilt, and evaluates the current x- and y- positions of the ball. These values are used for both visualization and generating haptic feedback.

Arduino sends the x and y positions of the ball to Processing using Serial communication. Then Processing generates the maze and visualizes the current level and the ball. The whole graphic tilts by changing the perspective of the camera view. Once serial communication between two starts, Processing starts the timer which appears at the top of the maze. Once the game is over, the timer stops and generates a congratulatory message.

Haptics

Vibrational motors

The vibrational motors provide haptic feedback to the user based on the ball’s location (relative to the left and right walls) and velocity. The amount of vibration is calculated by:

Both the position and velocity weights are values between 0 and 1, and the product between the weights is linearly mapped to a duty cycle value between 8 (highest duty cycle value where user cannot feel vibration) and 32 (maximum duty cycle to be sent to the motor). The position weight allows for more vibration on the side where the ball is located, and a faster ball allows for more vibration overall. For the velocity weight, the total velocity (calculated from x- and y- ball velocity) is used and this value is capped at a value v_max of 2000 m/s (iteratively tested) to get a ratio that is between 0 and 1.

We iterated on this vibration feedback many times. First, we tried applying vibration to the side that correlates with the direction of the ball velocity. When playing the game, this feedback was confusing because there was no indication of where the ball is located. After adding the position weight, we tested several equations for calculating the weight based on ball position, including a linear and sinusoidal relationship between ball position and position weight. We found that a power relationship provided the best haptic resolution across both low and high ball velocities.

Solenoid

The solenoid provided haptic feedback when the ball dropped to a new level or hit a wall. When its pin is set from HIGH to LOW, the solenoid physically hits a plastic wall that provides a “tap” feeling and clicking noise for the user. The solenoid pin needs to be quickly set back to HIGH to reset for the next wall collision.

So, when a ball drops to a new level, the pin is set to LOW (haptic effect and sound cue) and a counter is activated. When the counter reaches 5, the pin is set back to HIGH (no haptic effect and no audible response). When a ball hits the wall, the same sequence occurs but the pin is only set back to HIGH when the ball moves away from the wall by at least 2 pixels so that the solenoid isn’t activated multiple times when the ball is just continuously touching the wall.

Results

At the Haptics Open House, players found the game to be engaging because it was fun, immersive, and challenging. When the ball disappeared in “ghost mode,” many players relied on the sound and feeling of the ball hitting the wall to determine its location and then worked from there. However, this method was not very fast because the user had to wait for the ball to hit a wall each time that they wanted to gauge its position. Furthermore, since the solenoid produced the same cue for both sides, it was not a fully descriptive indicator, and the player would have to guess the side based on the tilt of the board. The most successful players focused most on the vibrational haptic cues to get a more precise sense of where the ball was located and how fast it was going. Players described the vibrational effects as “super realistic” because they closely matched the movement of the rendered ball. Players also reported that the sound of the solenoid increased the realism of the game because it sounded like the collision between a marble and a maze wall.

Future Work

To thoroughly evaluate the system, an experiment should be run comparing the speed at which users are able to complete the maze with and without haptic feedback. In measuring this difference, we could evaluate the effectiveness of haptics in navigation assistance. It would be particularly interesting to conduct this experiment with setups with no rendered graphics and with auditory isolation in order to eliminate the cues the player receives from the display and from the sound of the solenoid striking the plate. We could also create a simulation in which a ball moves invisibly around the screen and the participant must guess where the ball is located based only on haptic cues to evaluate the precision with which users can understand the haptic cues.

Improvements to the system could include wireless communication and battery power in order to make the device fully portable. Another issue that could be addressed is gyroscope drift. Over time, and especially when the user moves too quickly, the device’s angular calibration becomes skewed. Luckily, our game’s duration is short enough that there is not a significant negative impact on the player’s experience. By incorporating more complex filtering algorithms and integrating accelerometer functionality, we could preserve the accuracy of the angular measurements for a longer time.

According to user feedback at the Open House, it would also be useful to separate the haptic feedback for the ball hitting the wall and for the ball progressing from one level to the next. Both events are currently rendered by the same action of the solenoid, which caused some users to confuse the two events. In order to convey directionality in these events, the device could be outfitted with a mechanism that could shift the device’s center of gravity horizontally or vertically to convey the direction of the collisions.

Acknowledgments

Thank you Allison, Ankitha, Dani and Yiyang for their support throughout the course!

Files

Processing Code: Attach:maze_game_visualization

Arduino Code: Attach:maze_game_arduino_fin

Bill of materials: Attach:Bill_of_materials_haptic_maze

Handles STL, Solenoid Plate STL, Baseplate DXF: Attach:group10_final_hardware.zip

Circuit diagram for solenoid:

References

Appendix: Project Checkpoints

Checkpoint 1

For Checkpoint 1, we aimed to build the device and the virtual environment. Specifically, acquiring supplies (complete), 3D printing parts (complete, unless changes need to be made when testing), and coding the virtual environment (complete, not integrated yet).

For the physical device (90% complete):

- The handles have been modeled and 3D printed.

- The board (2nd iteration - the first prototype was Duron) has been laser cut from acrylic.

- The IMU has been purchased from Room36 and tested (it outputs tilt angles). There is some noise in the signal, so we might need to apply a smoothing function.

- The 5V solenoid has been selected and purchased from Amazon. The control circuit has been designed and was built in Lab64. The striker plate was modeled and 3D printed. It is unclear if it will produce a noticeable enough tap sensation or if its predominant signal will be auditory.

- Most of the wires have been soldered (only the right side motor wires remain disconnected as we figure out the best way to interface with the screw terminals).

For the virtual environment: The kinematics of the marble have been determined and implemented into Processing. A simulation of time varied tilt angles to test the kinematics and graphics were also implemented in Processing. Some elements of the kinematics and graphics that have been implemented include:

- Forces: from friction, gravity, contact with the wall (functions of tilt angle of haptic device)

- Wall contact: Wall was modeled as a spring-damper system when the marble comes in contact with it. Proxy positions are used to keep the marble from “breaking through” the wall

- The graphical y position of the marble is a function of the x location on the beam, and the tilt of the maze, and the game level

- Marble moves to the next level when it passes over a hole and is moving under a specified velocity

- The number of levels and locations of the holes are modifiable

- The marble will also disappear after a specified “Ghost Level”, while the kinematics/location of the ghost marble is continued to be computed

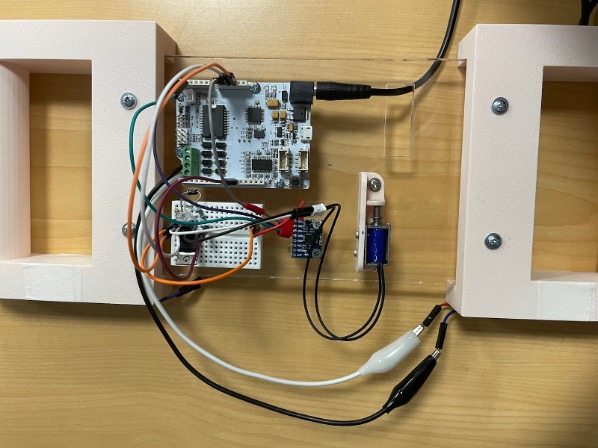

Shown below is a marble on Level 3, with 7 levels in the game. Green lines represent hole locations.

The Processing code was further modified for more realistic visualization. Considering the out-of-plane tilt of the board, a code was added to change the perspective as a function of the tilt, out-of-plane tilt, and the level(pending). As the tilt is now considered by changing the perspective, some equations on position has been changed The position of the hole is randomly generated. The height of the level is now modifiable When the user completes the final level, an effect appears and the ball falls off.

Figures below are the screenshots of level 5 in the game, and when the user completes the final level.

Figures below show the configuration of the board with out-of-plane tilt.

Checkpoint 2

Next Steps:

Example Video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=i_aLBql4Ufo