2024-Group 5

Overview

'+'''Project team member(s): Zahra Albasri, Judith Brown, Nivitha Mavuluri, Abhijit Pamarty +

The team.

Our project is a scavenger hunt using heat feedback, which we implemented using a Peltier element (white tile at the base of our black box) to provide thermal feedback. This system is used as a navigational aid in a Scavenger Hunt game. Players move through the environment by relying on the changing temperature, which increases as one gets closer to the hidden object (an orb). We wanted a novel feature in our system so we decided to use temperature variations as feedback, rather than traditional vibrational cues. Additionally, we decided to gamify the experience, motivated by our collective enthusiasm for creating a product that is not only innovative but also engaging and fun.

On this page... (hide)

Introduction

Our project aims to push our knowledge and experience with haptic technology using thermal feedback instead of the usual vibrations. We wanted to challenge ourselves by exploring a new area of haptics that we are unfamiliar with. The use of temperature variations as a feedback mechanism felt novel within our class, and set us apart from our initial idea of a maze. This project allows us to explore new realms of haptic technology while fulfilling our desire to produce an entertaining and interactive game. Our haptic device is appropriate because it combines multiple disciplines, including electronics, software development, and control systems, into a cohesive project. Peltiers are already the industry standard for thermal controls and have started to gain traction in thermal feedback applications.

Background

Current research for thermal feedback involving games predominantly focuses on its uses in virtual reality (VR) to provide a more immersive experience to users. One research paper focused on creating a bifunctional thermal system that could do both heating and cooling (Lee, 2020), as previous research had focused unilaterally on either heating or cooling. The researchers use a Cu electrode that has a polyamide on one side and a conductive elastomer on the other. The elastomer connects thermoelectric pellets, which allow for rapid thermal changes proportional to the applied voltage. The device is able to heat or cool depending on the direction of the current as per the Peltier effect. The device is fitted inside a finger motion-tracking glove for VR. For testing, participants were asked to pick up various objects of different temperatures. Participants were able to differentiate between said objects and the Peltiers were able to quickly return to room temperature following the contact.

The second research paper that we looked at for this project also used a Peltier thermal feedback, but it did it in conjunction with a pneumatic device that provided pressure feedback (Zhang, 2021). The goal of the scientists was to determine if a large temperature range (15 ℃ to 40 ℃) and a fast pressure actuation rate (7 Hz) could be used in VR and implemented on multiple parts of the body. The goal of this paper was to provide a device that enabled interpersonal interaction in a virtual space through the use of Peltiers and further proves that our teamís choice to use Peltiers was a well-founded choice.

Our final paper that we chose to look at for this project also utilized Peltiers for thermal feedback but removed them from directly contacting skin. Cai (2020) designed a pneumatic glove that pumped thermally regulated air into glove fingertips through the use of airbags. The air was thermally regulated in a separate compartment that contained four Peltiers which worked in tandem to rapidly change the air temperature before it was pumped into the glove. Participants were then asked to differentiate between different objects in virtual space without visual or auditory cues. Participants were successful in this task and fully able to differentiate between five different temperatures. This paper was the final validation that our team needed to move forward with using Peltiers for thermal feedback.

Methods

Provide a detailed description of your project, such that another student from the class could generally re-create your project/experiment from the report if necessary. (You don't need to document every screw, but the design should be clear.) Add images and videos as needed to support the description. You can refer to downloadable drawings and code in the "Files" section (later). You should divide this section into subsections, which can vary depending on your particular project. Here is an example set of subsections:

Theoretical Analysis

Controls

Designing the control system was an enjoyable challenge. We started by designing the circuit, creating a block diagram, and deriving a transfer function before implementing the controls. We also experimentally calculated the heating and cooling curves to accurately represent the circuit, compensating for some approximated values due to a lack of data. We included palm temperature data from a research paper to illustrate where the cooling curve dropped off.

Figure 1: representative block diagram of the system and expanded block diagram with PID controller

We created this initial block diagram and derived our control equations from it. First, the power supply provides the necessary voltage and current, with the H-bridge controlling the current direction through the Peltier module to enable heating or cooling. The temperature sensor measures the current temperature and provides feedback to the Arduino, which processes the data and adjusts the H-bridge based on a PID control algorithm. The block diagram outlines this process, showing the flow of power and signals.

Figure 2: Derivation of transfer function for electronic system

Using the block diagram we extracted the transfer function by using known formulas and oneís we found online. However, we were limited by the datasheets that were provided from the purchaser and didnít necessarily have the most accurate value, specifically for the H-bridge. We decided to continue with calculations to give us an idea and estimate of the transfer function, since it is helpful for understanding system stability and performance. In this step, key calculations include the H-bridge gain (0.7) and the Peltier module's heat transfer function, estimated from experimental data. The final result of which can be seen in Figure 2 . The next portion dives into our experimental results, such as a steady-state temperature of 97.64įF and a time constant of approximately 0.63, which are helpful in deriving these formulas as well.

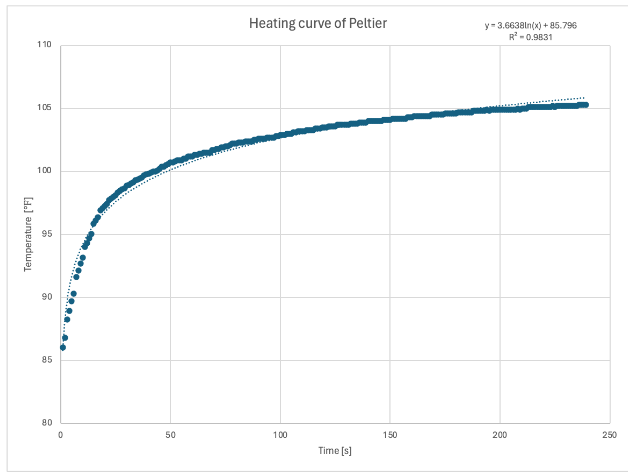

Due to a lack of clarity in the manuals of our commercial products, we opted to not depend on the values found within the manual and instead did experiments to determine how rapidly the Peltier would heat and cool. The experimentation was done as follows: The temperature sensor was fixed to the Peltier and the power supply was turned on to a current control of approximately 550 mA. 550mA was chosen due to the H-bridge having a limiting continuous current capacity of 600 mA. We then allowed the Peliter to heat up to a temperature of approximately 105 ℉ and recorded the time outputs. This was due to the Peltier struggling to maintain a temperature much higher than this at our limiting current. We then shut off all power and recorded the outputs. The resulting graphs can be seen in Figures 3 & 4.

Figure 3: Peltier Heating Curve

Figure 4: Peltier Cooling Curve

From the heating curve, we are able to pull the following equation for the logarithmic heat curve.

Temperature = 3.6638ln(time) + 85.796

The cooling curve cools exponentially, so we determined the log-based linear best fit line, which is as follows and can be seen in Figure 5.

Figure 5: Peltier Cooling Curve

ln(Temperature) = -0.0315ln(ln(time)) + 4.6697

Additionally, we chose not to cool the Peltier all the way back to room temperature, this was because the average palm temperature is around 92℉ to 98.4 ℉ (Bierman, 1936) and since participants would be in constant contact with the Peltier, it makes more sense for the Peltier to cool to palm temperature. To determine the control algorithm used in the arduino code, we applied the logarithmic heating curve equation to calculate the time required for the Peltier to reach the desired temperature. This calculation determined the duty cycle for the PWM pin. We found that whenever the Peltier was below the desired temperature, the duty cycle needed was greater than or equal to 100%. Since it is not possible to exceed a 100% duty cycle, we implemented a simple on-off control algorithm. This switch activates whenever the difference between the desired and actual temperatures exceeds 2℉. Since the Peltier surface cannot be artificially cooled, we did not utilize the cooling curve equations.

Hardware Design and Implementation

Experimentation

Sensors Validation

To test the sensor, we used an Arduino Uno along with Qwiic cables to enable I2C communication. We utilized SparkFunís STTS22H Temperature sensor to initially read the room temperature. To confirm that the temperature reading changes, we held the sensor and observed an increase in the temperature reading. Additionally, we tested it with Peltiers. The testing code is provided in temperature.ino.

Peltier Testing

We first tested the Peltier by simply connecting it to a power supply and confirming that the temperature reading changed. Then, we connected the Peltier to the Arduino using digital write commands and confirmed the temperature increase by touch. The testing code is provided in sensor_peltier.ino.

Creating the virtual environment

For generating the 3D environment, we used a rendering technique called ray-casting. This technique is computationally efficient because it renders a 2D environment as a 3D map without needing to calculate ray bounces like ray tracing and other common algorithms. The calculation is done only for each vertical line on the screen, causing the algorithm to slow down computationally only if the screen's x-direction is stretched.

The ray-casting algorithm starts by generating a 2D map of the entire space where a character is placed (Figure 6). The character has two degrees of freedom of motion - moving forward or backward and turning to change its facing direction. The 2D map is divided into a 16x16 grid, with each cell being either a wall (which the player cannot pass through), an empty space (where the player can pass through), or an orb (which the player wins by passing through).

Game mechanics

The playerís position is tracked using three coordinates: the player's X coordinate, the player's Y coordinate, and a theta coordinate for the direction the player is facing. Pressing forward or back adds a constant number of pixels to the X and Y coordinates based on the playerís facing direction using the projection of the direction vector. Collisions with walls are handled using a collision flag. If an input from the player would result in a collision, the collision flag is set to true, and the increment of the playerís position vector is skipped, preventing the player from moving into a wall.

The orb, which the player must find, is randomly generated each round. It first tries to place itself in a random position on the grid and then checks if the position is inside a wall. If the orb is inside a wall, the random number generator runs again to find a new position. This process repeats until the orb is placed in an empty location. The player moves around the environment to find the orb. When the playerís grid location matches the orbís grid location, the player wins the game.

Figure 6: the 2D map with the character represented as a dot.

3D graphics

The 3D graphics are generated through the ray-casting algorithm. This represents the 2D map as a 3D rendering by creating a projection of the 1D field of view from a 2-dimensional characterís camera as a 3D field of view by scaling the height of objects with the distance the object is from character For every x-coordinate on the screen, a ray is sent out that starts at the location of the character and a direction vector that is dependent on the direction the player is facing and the x-coordinate on the screen. The ray then moves through the grid, incrementing itself in steps equal to the distance it takes to reach the next grid square. By incrementing the distance in this way, we always ensure that the ray collides exactly at the next wall and not at an intersection that may or may not be on the surface of the wall. This is illustrated in Figure 7.

We first define the characterís direction vector by taking the cosine and the sine of the angle:

dx = cos(θ)

dy = sin(θ)

The camera plane is then defined by:

Dx = -fsin(θ)

Dy = fcos(θ)

The constant Ďfí sets the width of the field of view of the camera. Each X coordinate in the camera plane is mapped to the X-coordinates of the screen. For every x-coordinate, the ray direction (Φ) in the X and Y directions are calculated through the following formulae:

Φx = dx + XDx Φy = dy + XDy

Where X is the mapped spatial coordinate between 0 and 1. The delta distances (Δ) in the X and Y directions are then calculated for each ray:

Δx = (1 + Φy2/ Φx2)0.5

Δy = (1 + Φx2/ Φy2)0.5

Which then becomes

Δx = abs(|Φ|/Φx)

Δy = abs(|Φ|/Φy)

through simplification, where || is the length of the vector. As only the ratio between Δx and Δy matters for the ray casting algorithm, we can assume that the length of the vector is 1. Then the delta distance becomes:

Δx = abs(1/Φx)

Δy = abs(1/Φy)

The distance is then calculated by adding the delta distances in the x and y directions recursively, where we only jump by one square for every iteration that the algorithm runs. The distances of the character from the closest wall in the x and y directions are calculated and designated to be Sx and Sy, respectively. These distances are initialized with the length to the next closest grid space, and the following equation is done recursively until the ray encounters a wall:

Sx = Sx + Δx

Sy = Sy + Δy

Once a wall is hit by the ray, the ray ends up inside the wall. To bring it back to the outside, the values are once again updated using the following formula:

Sx = Sx - Δx

Sy = Sy - Δy

If the side hit is a vertical wall, the distance of the origin of the ray from the wall is designated as Sy . Otherwise, the distance of the origin of the ray is set as Sx . If the euclidean distance is H, the height of the vertical line that must be drawn on screen for this ray (h) is then calculated as:

h = k/H

Where k is a scaling parameter that sets the height of a wall that is at a distance of 1 away from the camera plane. Note that this algorithm uses the perpendicular distance of the wall from the camera plane and not the Euclidean distance as using the Euclidean distance would result in a fisheye effect.

Figure 7: a constant increment versus one that depends on the distance to the next wall.

To add shading, vertical walls are colored darker than the horizontal walls, and the bottom half of the screen is colored green, whereas the top half of the screen is colored blue. With this, the 3D environment is generated as in Figure 8.

Figure 8: the 3D environment

The orb is also designated as a wall, but it is colored yellow and is only drawn if the character is a set distance away from it. This is done by only updating the hit condition of the ray from the orb if the orb is a set distance away from the player Figure 9.

Figure 9: the orb.

The Manhattan distance of the player from the orb is simply calculated by finding the grid distances, which is how far the grid cell of the player is away from the grid cell of the orb in the x and y directions. The Manhattan distance is then returned to the Arduino, which then controls the Peltier cell.

Bridging Communication with Arduino, Processing, and Peltier

We began by confirming that the temperature sensor could accurately read the Peltierís temperature using sensor_peltier.ino. Next, we tested our control approach in the Arduino environment using distance_to_pwm.ino. We input different distances into the serial monitor, and the program linearly mapped these distances to desired temperatures. The sensor's feedback determined whether the Peltierís PWM pin should pulse high or low. This isolated testing confirmed the algorithmís functionality.

Finally, we integrated all components of our system by incorporating code from Processing into our Arduino control code. Initially, we tested in an isolated environment where Processing sent a simple number as a string to the Arduino. If the number was 32, an LED would light up, confirming communication between the two programs (communication_test.ino and test_sketch.pde). With this approach validated, we applied the same logic in graphics.pde and controller.ino. We monitored the temperature increase and decrease based on distance from the target by observing the current in our power supply and feeling the Peltier.

Results

During the open house, various users provided qualitative feedback on the game. Most participants successfully completed the game and provided insightful comments. One user suggested that the game end could be more celebratory, while another mentioned the need for more pronounced temperature feedback, as they couldn't feel a significant temperature difference at the end. Some participants who do not regularly play video games found aspects of the game confusing, such as not recognizing the orb upon finding it. Conversely, users with gaming experience found the temperature changes obvious and the game enjoyable, although one noted that the gaming controls could be improved. One user indicated that they felt heat through the walls and found it difficult to notice the temperature dropping. Overall, the feedback highlighted both the strengths of the game and areas for improvement, particularly in enhancing user feedback and refining controls.

Future Work

For future work, we plan to acquire an H-bridge that doesnít have a limiting current of 600 mA. The Peltier is rated up to 12V at 4A, and when testing the Peltier outside of the circuit, we observed much more drastic and rapid changes in temperature, which would significantly enhance haptic thermal feedback.

The controls of the game can be made better by allowing players to move the camera from side to side by the mouse instead of the arrow keys, as this is consistent with how other 3D videogames play.

Additionally, based on user feedback from the open house, we aim to implement several improvements. We plan to enhance the celebratory aspect of the game ending to provide a more satisfying experience for users. Increasing the temperature feedback to make the changes more noticeable, particularly at the game's conclusion, will be a priority. We will also work on making the game mechanics clearer, ensuring that users can easily recognize the orb when they find it. Improving the gaming controls to be more intuitive and less annoying will be another focus area, ensuring a smoother gameplay experience. Lastly, we will address the issue of users feeling heat through the walls and finding it difficult to notice temperature drops, potentially by refining the thermal feedback mechanisms and ensuring more distinct temperature variations. Using a graph distance measurement rather than Manhattan distance could also improve the user experience.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Allison Okamura for letting us borrow a tabletop power supply for this project.

Files

References

Lee, J., Sul, H., Lee, W., Pyun, K. R., Ha, I., Kim, D., ... & Ko, S. H. (2020). Stretchable skin‐like cooling/heating device for reconstruction of artificial thermal sensation in virtual reality. Advanced Functional Materials, 30(29), 1909171. Cai, S., Ke, P., Narumi, T., & Zhu, K. (2020, March). Thermairglove: A pneumatic glove for thermal perception and material identification in virtual reality. In 2020 IEEE conference on virtual reality and 3D user interfaces (VR) (pp. 248-257). IEEE. Zhang, B., & Sra, M. (2021, December). Pneumod: A modular haptic device with localized pressure and thermal feedback. In Proceedings of the 27th ACM Symposium on Virtual Reality Software and Technology (pp. 1-7). Yarnitsky, D., Sprecher, E., Zaslansky, R., & Hemli, J. A. (1995). Heat pain thresholds: normative data and repeatability. Pain, 60(3), 329-332. BIERMAN W. THE TEMPERATURE OF THE SKIN SURFACE. JAMA.1936;106(14):1158Ė1162. doi:10.1001/jama.1936.02770140020007 SparkFun. (n.d.). SparkFun Temperature Sensor - STTS22H (Qwiic) Hookup Guide. SparkFun. https://learn.sparkfun.com/tutorials/sparkfun-temperature-sensor---stts22h-qwiic-hookup-guide#software-setup

Appendix: Project Checkpoints

Checkpoint 1

Our initial goal was to develop a rough prototype by Thursday, 5/23. This prototype was intended to test temperature control based on proximity to objects and include basic game graphics. We anticipated that the hardware might not be fully polished and could involve temporary connections, such as taping. The game itself was planned to be a scaled-down version, possibly using a 4x4 grid instead of the final 16x16 grid. So far, we have made significant progress in several areas. We have acquired all the necessary electronic components for our hardware and have begun constructing our physical setup. However, we still need to acquire the gloves, which are critical for the final setup. We have tested the Peltiers using a 12V battery. The graphics for the game are completed, marking a significant milestone in our development. However, the coding of the transfer function and controls analysis still need to be completed. The primary reason for this setback is that we had to deliver our presentation earlier than expected, diverting time that would have been dedicated to coding. Additionally, the hardware components only arrived two days ago, delaying the start of our physical setup. To catch up and ensure we meet our project goals, we plan to devote extra time over the weekend to complete the first working prototype. Specifically, we have outlined the following steps: - 5/25: Develop basic code for the Peltiers and test integration with the game graphics. - Stretch Goal (or complete on 5/27): Build the glove hardware. - Stretch Goal (or complete by 5/30): Test the full system. Moving forward, we are adjusting our timeline to ensure that we can integrate the hardware and software components effectively. By concentrating our efforts over the next few days, we are confident that we can achieve a functional prototype that meets our initial project goals.

Figure 1: Circuit Wiring

Figure 2: Rendering of 3D environment

Checkpoint 2

We had some delays with our hardware due to an error on our part which required us to order more parts. And then on top of this, Amazon delayed the parts that we ordered so we have had a delay in the final build of our project. We also recently found a more controlled power supply because we wanted to have multiple checks on the temperature so that it didnít exceed safe temperatures for humans. Thus far we have a glove, we have soldered out Peltiers, we have the power supply, an H-bridge, arduino, alligator clips, wires, and temperature sensors, and had a rough prototype that we are testing before we put it all together. We finished the software development of the Arduino and the processing code. We are now working on debugging and triple-verifying that all our sensors are working properly. We have tested our temperature sensor readings on Arduino, and are working on calibration. All in all, we have met 3 out of four of our checkpoints and feel confident in our project.